Today is the 76th anniversary of the end of World War 2 – and a chance to salute the men who fought to the bitter end to defeat the Axis powers.

The war in the European theatre ended on 8 May 1945 when the Allies accepted the unconditional surrender of all German forces, and VE Day – Victory in Europe Day – was celebrated by the victorious nations across the continent.

But the Japanese continued to fight, and Allied sailors, troops and aviators in the Pacific and Far East faced the troubling prospect of having to batter the Emperor’s forces into submission – a task which promised to be long and bloody for both sides.

From a Naval perspective the greatest presence in the last months of the war was the so-called Forgotten Fleet – thousands of Royal Navy and Commonwealth sailors manning a formidable force of more than 200 warships, auxiliaries and submarines spearheaded by aircraft carriers and battleships that dovetailed into an event greater force including the Americans and Australians.

For almost two years the Japanese had been steadily forced to retreat towards their homeland, prised out of strongholds or pinned down as they fell back in a series of vicious actions – the Philippines (1944-45), Iwo Jima (March 1945), Saipan and Okinawa (July 1945) amongst them.

With no hope of victory, initial plans to defend the Home Islands were laid as early as 1944, and in hindsight make chilling reading – they amounted to wave after wave of suicide missions by aircraft and motor boats with the intention of inflicting as much damage to the morale of the Allied invaders as possible.

In effect, the Japanese people were expected by their military leaders to fight to the point of extinction.

But another approach began to manifest itself as summer 1945 arrived – prompted by the Emperor, Japanese leaders were urged to seek other ways to end the fighting, perhaps by seeking a form of peace deal through intermediary nations.

On the Allied side, Churchill, Truman and Stalin met at the Potsdam Conference in July-August 1945, at which both Europe and the Japanese situation were discussed.

A Declaration at the end of the Conference called for unconditional surrender of the Japanese and threatened ‘prompt and utter destruction’ as the only alternative – and by this time the Manhattan Project had borne fruit – the Allies had a viable nuclear weapon.

On the morning of August 6 the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay dropped her deadly cargo, and the Little Boy atomic bomb detonated over the heart of the city of Hiroshima, releasing a deadly flash and blast, followed by widespread radiation.

The number of casualties is impossible to calculate – many close to the detonation were vaporised, leaving nothing to identify them; other bodies were charred beyond recognition in the fires that followed, and others died of radiation sickness and other diseases over the following days, weeks, months and years. Estimates vary widely, but it is thought between 65,000 and 150,000 died as a result of the bomb.

Three days later, with the Japanese scrambling to work out what had caused the near destruction of Hiroshima (they had their own rudimentary atomic weapon programme, and found it hard to believe the Allies had succeeded in building a working bomb), Nagasaki was also targeted.

This time the bomb – Fat Man – killed up to 80,000 people, and Truman issued another statement threatening to continue to use nuclear weapons until Japan’s capacity to wage war was destroyed. Only surrender would stop the carnage.

Still the Japanese leadership debated their next move, but Emperor Hirohito had had enough, and sanctioned the surrender – though still they quibbled over the extent of such a course of action.

Eventually, under the threat of further atomic bombs and from the Russians in Manchuria, agreed to Allied demands, and on August 15 (VJ or Victory over Japan Day) the Emperor broadcast to the nation that, with the war having developed “not necessarily to Japan’s advantage”, the Empire “accepts the provisions of the Joint Declaration”.

The news was greeted with wild enthusiasm by the Americans, and meant that the men of the Forgotten Fleet could at last contemplate a return home – though for many that would not happen for many months, as there was much to do in terms of restoring the region to some sort of normality.

Allied prisoners of war had to be freed and repatriated, former territory seized by Japan had to be re-established, and there were still areas to the Pacific, Far East and Middle East to be cleared of stubborn combatants, then protected and patrolled.

In many cases, British sailors and Marines made their way back to the UK through the end of 1945 and into 1946 almost unnoticed, greeted by families and friends but without the sense of celebration that accompanied VE Day, leaving many dismayed that their war service did not receive the formal or public recognition that had been afforded to those who were in the European theatre, and hailed as heroes, on 8 May.

As it happened, the British Pacific Fleet did indeed fight to the bitter end of the war – the last Japanese warplanes shot down in anger were destroyed by gunners in the Forgotten Fleet on VJ Day itself.

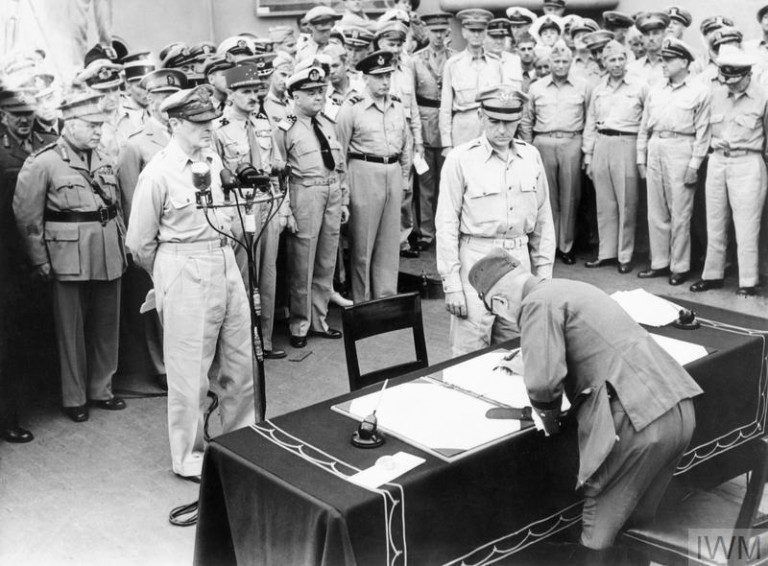

A formal surrender ceremony took place on the morning of September 2 on board American battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay; the Americans mark this date as VJ Day.

Today’s image, from the Imperial War Museum collection (© IWM A 30427), is of the surrender ceremony in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945, with General Umezu Yoshijiro signing on behalf of the Imperial Japanese Army on board USS Misouri